From Chain Smoking to Chain Giving: Profile of Venkat Krishnan

Aug 14, 2009

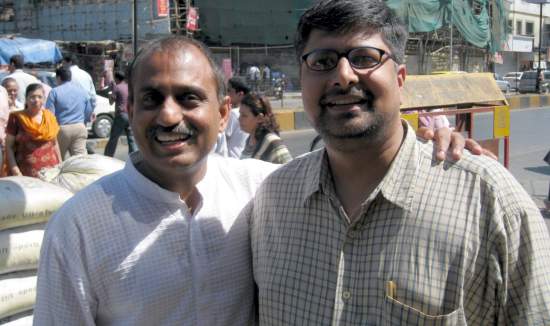

When Venkat (right), Jayesh-bhai (left) and I last met in Mumbai, we brainstormed about inspiring greater giving in India. Whenever Venkat runs into a good idea, he goes at it with full gusto -- from running a wholistic school in Ahmedabad to implementing his idea of a Bombay Marathon (that has raised 100 million ruppees for nonprofits!) to GiveIndia that has remarkably shifted the entire philanthropy sector of India. Like clockwork, inspired by a suggestion Jayesh-bhai made at our lunch, comes his latest venture -- Joy of Giving Week that culminates around Gandhi's birthday. And it's taking India by a storm, with the likes of Sachin Tendulkar getting behind it whole-heartedly.

Having known him for close to a decade, one thing would always bug me -- not enough people knew his inspiring personal story! Stuff like the fact that all his possessions fit into 2 suitcases. I always threatened to write his profile myself, but fortunately, Rashmi Bansal beat me to it, :) in her book 'Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish':

He’s worked with a newspaper, a television channel, and as a principal of a school. Venkat then launched GiveIndia to promote the culture of ‘giving’ in India. He is an entrepreneur but his mission is one with a difference.

“Had Venkat Krishnan got admission in a convent school in class 5, he may have been your regular investment banker type today. But six years spent an ‘Airport High School’, where a large number of students came from slums and chawks, changed Venkat’s life. It made him who he is.

“From class six of seven, I started feeling extremely strongly about inequity in society. I could see that there was a guy in my class whose father works in Dubai. So the family was well off, they have a two bedroom house. They would eat biscuits for breakfast which is a luxury. And there is another guy in the same class who lives in a slum in Kajuwadi and his father is a garage mechanic. And they would always buy "dus paise ka shakkar aur pacchis paise ka tel", that too when a guest comes to their house.”

And to Venkat that seemed fundamentally wrong. In a country where most of us are conditioned to simply ‘look the other way’ that makes Venkat a seriously different kind of guy. And that difference reflects in every choice in life he’s made. We are meeting in the lobby of a suburban hotel. Venkat lives somewhere close by but hesitates to call me home. “The house is too small,” he mumbles. Not that he really cares what I, or anyone else, think of his life, or lifestyle.

Venkat’s nickname on campus was ‘Fraud’ which is ironic because both in the honesty with which he speaks to me, and the actual work he does, Venkat is one of the most genuine people I have ever met. And genuine people are always an inspiration”

Here's Rashmi's full profile of a guy who has dedicated his life to promoting giving in India:

Venkat Krishnan grew up in what you would call an ‘ordinary middle class home,’ the youngest of three children.

“My dad used to work in Godrej, and I have had one of the best childhoods one could possibly have. Very caring mother, always making sure you ate all the vegetables and all that.”

And yet, it was extraordinary in some ways.

“Dad is an engineer and he is one of those gizmo type guys meaning out house is a garage at all points in time. Even now, we will have a black and white 1971 television lying somewhere in the attic because he will always aspire to repair everything.”

From the time Venkat was five, he was part of these projects. Late in the evenings after coming home from work, dad would be busy tinkering with a Bush radio. Venkat would hold the soldering wire or the pliers – involved in some way.

“I think one of the best thinks that happened in childhood and particularly with me (I think the youngest kid in the house always gets the best treatment) was lots of exposure and learning right from early in life.”

When Venkat was about 10 years old, his dad worked with a company, which manufactured speakers for export to Denmark. When they had to get a die or a mould made, he would take Venkat along. Few kids get exposed to what is grinding, what is turning in a lathe, what is oil hardened natural steel, and what is mild.

Later, as a teen, Venkat recalls hanging out at Sakinaka, where there are many small scale industries. Accompanying his dad, Venkat would watch, figure out things, and give ideas on how those people could improve productivity.

“Another interesting thing – we used to play a lot of ‘games’ as a family when I was young. Late nights, over the weekends, all five of us used to do four digits by four digits multiplication sums and see who finished first!”

When in class four, Venkat discovered the system for multiplying end digit by end digit numbers in one line without having to write down steps. Much later he found it was called the ‘Trachtenberg System.’

The bottom line is a spirit of curiosity and of ‘learning to think independently’ was aroused. And that’s a critical characteristic you will in most people who are entrepreneurial in nature – they will tend to not accept what is told to them at face value but take the available information and process it on their own.

And then there was the impact of schooling.

Up to class five, Venkat studied in what we call ‘good schools’. But when his dad switched jobs and shifted to Andheri, he ended up joining ‘Airport High School’ which is, by all standards a very average kind of school.

“I think that was the most life transforming experience for me. When you go to convent school, you actually don’t see the whole spectrum of people. It will be middle class dominated.”

At Airport High School, much of the school was from the ‘lower middle class,’ Venkat was regarded as relatively ‘well off.’ One day he would be playing at the house in which you are born. That’s the most significant predictor of your likelihood of success. There will be exceptions. There will be the odd Dhirubhai Ambani who was born poor and went on to become a star. But those are extreme examples.”

No doubt something we all know, but don’t feel for, because we have not personally experienced it. In fact, the trend is to protect your kids from this knowledge by sending them to an elite international school full of elite international kids like your own.

Far, far away from the ‘real India.’

By class seven, Venkat was clear there was something wrong with the way things were and wanted to do something about it. At this stage Venkat studied the ‘Communist Manifesto’ (he knew it by heart, word by word!). George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’ was another book which had a huge impact.

Engineering would have been a logical career choice but by class 10 Venkat was clear this wasn’t the thing for him.

“I was quite fascinated by engineering, but felt very clearly that I didn’t want to become an engineer. I wanted to do something that could make a difference.”

So Venkat decided to take up commerce. He believed that it would help in his ultimate goal – of making a difference. Unfortunately, even though he hardly studied, Venkat managed to secure a state merit rank in the SSC board exam.

“My father is a very pushy character. He dragged me to Parle College and got me admitted to science. So le liya admission. I passionately hated biology so I took electronics as the option. And somehow I decided not to do commerce at that state. In hindsight, I think that was a very wise decision. You learn far more in science.”

Venkat refused to sit for engineering entrance exams and opted for BSc in Mathematics instead. Ironically, he coached several others and seven of his friends actually got through to engineering colleges. Meanwhile he essentially ‘freaked out’.

“I used to play 6-7 hours of cricket everyday. And I had also started smoking. So a typical day would be sitting on a katta, outside the college, looking at girls, eve teasing them, smoking and lots of cricket and whiling away one’s time.” An admission which will shock and awe most kids today, who dream of someday making in to an IIM!

However despite failing in all subjects in the prelims and studying for about a week, Venkat managed a 92% in the HSC. Once again, dad tried to interest him in joining a local engineering college, but by this time he had grown in conviction and learnt to say ‘No’.

“I was passionate about mathematics as a subject, still am. You can get me excited about maths like this in thirty seconds.”

Venkat secured a merit scholarship for studying maths. Of course, he hardly ever went to college; instead he excelled in extracurricular activities.

“At the end of every term, I would go with a long sheet with day by day details of where I had represented the college – in chess, debating, dramatics, JAM and so on. We also set up a Rotaract Club in the college, which was very exciting. I would say my first entrepreneurial experience in a sense.”

Parle College was a fairly traditional, Marathi kind of a place where there was no culture of participating in intercollegiate competitions apart from classical music. The Rotaract Club made a huge impact in terms of transforming the environment in the college, making in more cosmopolitan and encouraging young talent.

“I was the founder and president. It took a lot of effort to convince our college authorities to allow something like this. According to them, it was very western. They believed that girls wearing skirts is not a good idea and with Rotaract all these skirt-wearing girls would come to the college.”

In hindsight, Venkat realizes he was good at understanding people from opposite ends of the spectrum – the ‘pseud’ category and the ‘dehaati’ category. He had the knack of seeing the perspective of others, and somehow balancing it all.

The activities of the Rotaract Club included going to TOMCO (Tata Oil Company), meeting the GM and convincing him to come and give a talk on marketing as a career to students.

“We actually used to meet people, get them to college and organize a career guidance fair entirely on our own. Coming from the classic middle class upbringing, it was a liberating experience, being able to do my own thing, meet new people, take risks, buy things, succeed, fail, whatever.”

The result was that Parle College blossomed. In fact, they won the ‘Best College’ trophy at Mood Indigo in a particular year.

Which again goes to show that it’s not important to merely get into the ‘Best College’. But to make the best of your college life, wherever you experience it.

So after all this, how did IIM happen?

“That’s an interesting story. Three weeks before my second year final exams in college, our head of department in statistics called me and another guy and said, ‘I don’t care what you have done in intercollegiate bullshit. You have not attended any statistics classes, I am going to fail you’.”

Finally he relented and gave them a separate test as a ‘pre-qualifier’ to even attempt the exam. Venkat got 20 out of 20 on that test and the crisis was averted. But as a consequence, he got deeply interested in statistics.

“Firstly because it is so much about numbers and I am passionate about maths. And secondly, you realize how much impact it has on peoples’ lives. Look at the green revolution that has happened, or the top scientific discoveries…”

“What does a scientist do? He designs the experiment. But that is actually only 25% of the job. 75% is analyzing the data you got from the experiment, creating hypothesis and testing them out. Which is all statistics actually.”

Venkat gave up his maths scholarship and decided to major in statistics. Side by side he studied French and Cost Accounting. “People say balance sheet is difficult but I have never been able to create a balance sheet that doesn’t tally,” he says matter of factly.

“So basically things came quite easily to you,” I observe.

“Yes, things came quite easily to me.”

“Then that becomes difficult because you can do anything,” I add.

“To say that it’s difficult is not fair. I would say it makes life easy. You can pick and choose what you want to do.”

And at some point Venkat chose to take up management, although not for the usual reasons.

“One of the fears I started having while doing BSc is, am I being extravagant? Because I am not from a rich family, right. I had to build my life.”

The idea of becoming a sales rep running around selling pharmaceuticals did not appeal. So more as a ‘de-risking’ thing, Venkat took the CAT exam.

“I managed to get section A of IMS coaching material from one of my seniors, free of cost. I studied from that. My CAT entrance was terrible. At IES school in Dadar, I was put in a KG class where the benches were so small that I had to sit with my legs outside for the whole two hours.”

“Calls came from all four IIMs. At the IIM Ahmedabad interview Professor GS Gupta was on my interview panel. In those days, on Doordarshan, in weather forecasts, they used to give decimal temperatures of all cities.”

Gupta asked, “You are a stats grad. Tell me what is the probability that all eight decimals will be different. A guesstimate.”

I said, “Less than five per cent.”

He said, “I am delighted. You are through because this is the first time anybody has given the correct answer to this question.”

Venkat had also taken the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) entrance test. On 3rd July, 1999, when he was on the IIM campus, the MStats admission letter came.

“I think that was the toughest decision I went through in my life. From six in the evening till three in the morning, I was agonizing over what to do. My passion was to do statistics, I wanted to go to Calcutta. But somehow the idea that the MBA degree gives you much more access to more opportunities, financially you will be much more well off, that in turn is empowering.”

Finally he opted to stat at IIMA.

“First 1.5 months, I was very scared because everybody is a Stephen’s topper and IIT this and IIT that. I did extremely well. My first mid terms GPA was 3.7 or something like that. Then I stopped studying.”

Why?

“I am not interested in doing well academically.”

So what was he doing?

“I was sleeping. You can ask anybody in my dorm.”

And thus, Venkat was nicknamed ‘Fraud’. People used to believe that after everyone slept, he must have been switching on his table lamp and studying. Because he did so well, getting A’s in tough quant courses without ‘any apparent effort’.

As usual, Venkat did find ways to use his time constructively.

Learning to play the keyboard; reading in the library, whenever he had free time. Much of it on the subject of higher education. The system of memorizing dates and formulas, he strongly believed was killing human potential. If you let young people fall in love with a subject, imagine what they can do to build a better world!

Clearly, Venkat was not headed for a mainstream corporate career. The idea was how to leverage this degree to make a difference. IAS was one possibility. A summer job with Khadi Village Industries followed. The project was to develop a model to market khadi without rebate.

Soon enough he realized a similar project had been done by IIMA’s Professor Vora and it was gathering dust in their library. What’s more, working with the CEO of KVIC, an IAS officer, made Venkat realize how weak the bureaucracy was in terms of decision making. He realized that IAS was not his cup of tea.

Then, LEM happened.

Venkat had opted for the entrepreneurship package – courses like New Venture Management, PPID (Project Planning Implementation and Development) and LEM (Laboratory in Entrepreneurial Motivation). Plus, he did two IPs (Independent Projects) on entrepreneurship.

The first IP was on the feasibility of private enterprise in education, especially vocational education. The second was on the feasibility of the private sector in rural finance (the term microfinance was then unheard of).

By this time he was quite confident about wanting to become an entrepreneur, at some stage in life. But it was also clear that even if he became an entrepreneur, it would not be something like IT, but about ‘making a difference’.

“I remember my first reflective note for the LEM class – I see myself as an instrument or tool that is available to society. And my choices should be guided by maximizing the returns that I will give to the society. So I will not do something just because I like it, but because that is the best use of my time for the society’s benefit.”

“If I think that I will serve society best by becoming a teacher, then I will teach. If I think I will help society best by becoming a businessman, then I will become a businessman. I will do whatever it takes.” The guiding principle was, and remains, to restore the maximum amount of fairness to society.”

Come placement and you know Venkat is not going to go for the usual companies.

Actually, he almost joined aatawallah near Vapi who had participated in placement that year. He was offering a fancy salary, but the chap said the job is to help run the atta chakki and help him save income tax. That put Venkat off completely.

“I would have joined him, if he had been an honest guy. Because he was asking you to run the business as a CEO,” says Venkat wistfully.

And that’s something which makes a lot of sense for any MBA with ambitions of becoming an entrepreneur. Joining a company which may not be the biggest or most glamorous name in the business, but a place where you get to be hands-on and get a 360 degree experience of actually running a business.

Eventually he settled for TOI – a day six company – as media too is an opportunity to ‘make a difference’. And like every experience, he sought out and savored for its duration, this stint too was about learning, about growth, about invention.

Being EA to Mr. Arun Arora, a director on the board, Venkat interacted closely with Sameer Jain, Vineet Jain and Ashok Jain. He worked on IR problems faced by the company, drafting the letters sent to the Union during a strike.

Then there was a salary restructuring project where Venkat argued that journalists should be paid better. He also helped write a far reaching document called ‘Looking Beyond the Horizon’ which envisioned the technology strategy for the company. Much of which actually got implemented.

Then Venkat’s boss joined Sony Entertainment Television (SET) as CEO. The condition set by the Jains was that Mr. Arora could not take away more that one employee. They person he chose was Venkat.

“I was not keen to leave but he had already asked for me. Plus SET paid me 40k a month which was big money in 1995. My brother and I had both taken student loads, plus dad had quit his job, tried a business and failed at it.”

The SET job help the opportunity to clear off family debts, allowing Venkat the freedom to then do whatever he wished. Four months salary was all it took to pay off everything. And as always, Venkat is grateful for the exposure he got at SET.

“Even though it was a very short six month stint, I got to work with the promoters and build the business plan of the company. I made the most critical sales pitch to Fulcrum, and to M. Venkataraman, the head of media at HLL.”

But it was time to move on to something else. In a field much clearer to him. The field of education.

In 1995, Sunil Handa sent out a note to a number of IIMA alumni and former LEM students about a proposed school project. However, the idea was a residential school for the middle class and that did not excite Venkat. Until a close friend and batchmate Sridhar (DD) stepped in.

DD was working with IBM at that time and he was excited. He said, “Let’s go and meet Sunil Handa. Let’s offer to volunteer the weekends.”

Venkat was very passionate about teaching and said, “Chalo, jaate hai.”

But, once they got there, something happened.

“I told Sunil Bhai that residential schools are cut off from real life. Even IIT and such places, you are so cut off from reality that you tend to live in islands. You don’t know what it means to be a poor guy in India. You don’t know what it means to live in slums. You don’t know what it means to struggle to exist.”

Why not instead set up a day school? What’s more, there would be a certain quota of students from the poorest of poor families. Sunil agreed and by the end of the meeting both Venkat and DD decided to quit their jobs. This was August 1995.

“Both of us were in the middle of product launches, so when they said please stay back till the launch, it seemed like a fair kind thing to do. I finished work at SET on 14th January, 1996 at 7:30pm. At 9 o’clock I took the flight to Ahmedabad.”

And thus started the Eklavya Chapter.

“We spent about a year and a half researching education, figuring out what is a good school. So we traveled all over India. We spent three weeks in Europe also, doing some things together then branching off. Having conversations till three in the night on everything from what is the best method of education, to what should be the discipline policy of a school. Right down to how we should design our chairs.”

The point being that whenever you look beyond business, into the things that make a difference to the quality of our lives, we somehow think there’s no need to apply scientific thought.

“In India you find that the guy who is designing a mall is designing a school the next day. And that architect will have zero understanding of what you mean by an educational environment. So kindergarten children are climbing six inch high steps, urinals are designed at a height where the child actually has to stand at the edge of his toes.”

This is why the ‘immersion’ experience was so important.

“Between us, we must have read at least a thousand books. I am not exaggerating. We would read an average of three books a week, on pedagogy, on Montessori method and so on.”

Responsibilities had been divided – Venkat was setting up the day school, Sudhir (an IIMA PGP ‘ 94) was setting up the residential school, and Sridhar was setting up the teachers training institute.

In March 1997, the day school was ready to launch. And it was an absolutely humbling experience.

“All four of us were IIM graduates, right! So we had this huge thing that the day we announce admissions, there is going to be a mile long line of people who want to get admission to our fantastic school. So 27th March 1997, we put ads in the paper and Sunil Handa came with a camera to video record the queue.”

A total of five people came to inquire. The team was shattered. At 1am they convened and wondered aloud, “Boss abhi karma kya hai, it seems as if the world doesn’t want us to set up the school.” Then they decided, come hell or high water, if we get even 10 kids, we are going to start our school.

For two months after that, they did door to door sales. Sridhar, Sudhir, Venkat, and their teachers.

“We would knock on people’s door, with a brochure in our hands and say, ‘Good afternoon madam, we are here to talk to you about a new school that we are setting up in your city. Would you like to know about it?”

“The good thing is, more than 70% of the people let us into their homes. They would sit, they would hear us, give us chai and biscuits. The fact that we were from IIM made a big difference. After two months of door to door calling, we closed the admission with 34 kids for class one, two and three.”

The goal had been to get 24+24+20 so getting 34 students that too with great difficulty, did not feel like an achievement.

“If you ask me, this was my closest brush with ‘failure’ in life. But we saw through it – having each other for support was of huge value.”

Of course, this was just the beginning. The school started and a fascinating journey began.

It was all about teamwork. There was a great sense of togetherness, a team of teachers who were extraordinarily passionate. Some of them would work till two in the morning, then lave their homes at 6:30 am to reach the school at 7:15 am. All bound by a sense of purpose, a commitment to something larger than themselves.

Parents were delighted with the experience. The following year when admissions opened, all 240 seats filled up. Some had to be turned away. Eklavya was the ‘coolest school of Ahmedabad’ within one year of existence.

How did it all happen?

“I think if there is passion in the environment, people pick it up. I have seen it in every place I have worked in. Nothing energizes people like seeing other positive people, and integrity of course. Integrity with them are doing something with the desire of doing something good and not their own gain. That drives people extraordinarily.”

Four years after getting into the Eklavya Project, two and a half years as principal of Eklavya school, Venkat decided it was time to move on.

Why?

“I am a my-way-or-the-highway kind of guy. And I guess I decided it was just time to move on.”

Like every time he started a new chapter in life, Venkat had no clear plan of what next. But some thoughts were in his head.

During the one and a half years of traveling for the Eklavya project, Venkat recalled meeting a lot of organizations including NGOs that were doing really good work. Very committed, very passionate people, yet somehow nobody had even heard of them. That bothered him.

Then in 1998, Venkat spent two months in the US, traveling all over. It happened like this – Sudhir, Sridhar, and Venkat had all been saving to buy a house. But it dawned on Venkat one fine morning that he didn’t really want to own a house. A rented house would suit him fine, especially because he did not plan to marry.

Soon after, Venkat noticed an ad for a round trip to New York by Royal Jordanian Airlines, for Rs 26,000.

“I was always fascinated by the US as a country, especially after the Soviet Union collapsed. I wanted to find out, what is it that makes US as a country tick? I also figured that I was not doing any of the conventional things that people do for their parents, right! So I decided to encash the lakh and a half rupees I had saved, and bought three round tickets to the US where my brother was then based.”

With the remaining money, Venkat bought a VUSA pass to travel to 12 cities across the US – Cincinnati, New York, Washington, New Jersey, Burlington, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Crazy amounts of travel at dirt cheap prices.

In every city he knew somebody, so he wrote them a mail saying, “Let me stay at your place for two days.” And every place he went to, Venkat would go to a school.

“I was running a school and trying to understand the American education system. One of the things that hit me really hard about the US was that people in that country have a sense of ownership for their country. People care.”

“That really hit me hard and I felt, that’s what we need back home in India. You take a typical guy who goes to IIM, who comes out, works in an investment bank or wherever. We are obsessed about our own careers, and we couldn’t care less about our country. I think that has to change, that’s not on.”

“After all, those of us who have gone through IIMs and IITs have been subsidized by the poor – the guy living on the road, when he his two bit of a matchbox and pays sales tax. The second part is that we were lucky to have been born where we were. What if I were born as a garage mechanic’s son?”

On returning to India, Venkat did a lot of research. At one level he found the Rockefellers, Carnegies, and now Bill Gates who’ve given away their wealth. But what about the contribution of ordinary citizen towards the betterment of society?

“In America, every school that I went to, every working day, there would be mothers from middle class families, sitting in the classroom and helping the teacher with a group of Hispanic students who are weak or children with learning disabilities. There was this sense of civic responsibility, that as a citizen it is our duty to help.”

“In a town called Burlington in Vermont, they were going to close down one of the three high schools. And they had a town hall meeting. That’s the first unthinkable thing, right! If BMC wants to close down one of its schools, I don’t think they will actually organize a consultation. But here they actually had a discussion, and it was well attended.”

“Most importantly, the affluent people in town said, ‘Close down the school nearest to ours, because we all have cars and we can afford to send our kid there.’ Whereas in India, Malabar Hill, people will say, ‘Suck the water from Vaitarna and give us water 24 hours a day. And too bad if Mira Road, which is a few kilometers away doesn’t get water more that half an hour a day’!”

In the ‘Market is Everything Era’, the middle class in India has lost that sense of purpose. And Venkat is passionate even in his dissection of the problem.

“It is the middle class who were the authors of the freedom struggle, not the rich, not the poor. Gandhi was spot on.”

“I cry every time when I think of 15th August when were all celebrating freedom and he was in the middle of a village near Calcutta saying, ‘Now is not the time to celebrate freedom. Now is the time to fight the next enemy that we have, which is religious intolerance’. What courage it takes for a guy to think like that’!”

Freedom from British is the first milestone in my life, my next milestone is freedom from poverty, my next milestone is freedom from intolerance that is what we need!

“We need the best minds in the country to think, ‘What is the human ideal that we aspire towards?” Rather that what is the next 30 crore flat that I can buy for myself, or whatever else that I can do for myself.”

He hastens to add, “Please have a 30 crore flat, but don’t be blind to the world outside your window.”

The time was ripe. A growing number of Indians were beginning to do well for themselves. They were going to have everything that they could possibly want very early in life. Could we not then start building a culture that helps give back?

And thus was born ‘GiveIndia’, an organization dedicated to promoting and enabling a culture of ‘giving’.

When Venkat quit Eklavya, a couple of things fell in place. He had bought a home PC and was fascinated by the power of the internet.

The net was also a useful source of information. Venkat found out that in the US ‘giving’-in all forms – formed 1.8% of GDP or $180 billion dollars in ’99-00. The corresponding number in India was less than 0.1% or 0.2% of GDP.

And here’s a startling fact – the poorest people give the most, as a percentage of income. This is true not only in the US, but all over the world.

Venkat realized that on the one hand there were organizations and people who are passionate and doing amazing work which nobody has heard of. On the other hand, there is an opportunity to give back.

“I used to write to batchmates, friends, people I know who are doing well asking them, ‘Why you don’t give more?’ The first questions was, ‘Who can I give to? I don’t know if my money will be used properly.’ That typical cynicism that we have in our system is perhaps justified.”

So the idea was born that one can create an organization that showcases NGOs doing good work and enable those who wish to ‘give’ a platform to connect with them. And thus, help create a culture of giving back.

One good think that Venkat learnt in Eklavya, and credit to Sunil Handa for that, is whenever you have a good idea, write a note, to circulate it, show it to people, get their thoughts and reactions. So he wrote a two page concept note, mailed it to some people and got a lot of interesting feedback. And then Venkat started meeting people to turn the idea into action.

He went back to The Times of India, they were not interested. He met Shekhar Gupta at The Indian Express. Shekhar loved the idea and said, “Come and help me run the paper and use Indian Express as a vehicle to build the idea of GiveIndia.” Venkat declined.

Gagan Sethi, who runs an NGO in Ahmedabad called ‘Jan Vikas’, was very encouraging and even offered to seedfund the idea with Rs 10-12 lakhs.

“In hindsight, one of the best things that happened with the IIM degree was, it gives you access. It opens doors for you like nothing else does. I don’t think a person who doesn’t have an IIM degree would have been able to get access to Shekhar Gupta, be able to convince him, to support an idea like this. And I think the kind of networks you get being in the IIM system are invaluable.”

Through this network, Venkat met Nachiket Mor of ICICI. He said, “You know, we at ICICI have been thinking of doing something exactly like this. So why don’t you set up the organization! We will fund you, give you all the support you need, help build it. We will give you the license to your our brand if you want it.”

“And I would say I have never been really lucky. The amount of support I have got in my life is mind boggling. ICICI and Nachiket in particular, hats off to the support they have given. Unquestioning support. Any time I need his help, he is available. Anytime we are going through a difficult patch, they are with us.”

Any they have never sat on our heads and said, “You have to do it this way and why aren’t you doing this.”

With this support, GiveIndia formally started in April 2000, five months after the idea was born. GiveIndia is structured as a philanthropy exchange. Just as you have a stock exchange, which connects companies with investors, Give connects worth NGOs with donors.

“I would say GiveIndia is actually one of the founding organizations of the idea of philanthropy marketplaces globally. After us, a lot of other organizations were born. Like Global Giving, in the US, there is now one in South Africa, in the Philippines, in Columbia, Argentina, ect. Most of these organizations were set up between 2000-2003.”

The first version of GiveIndia was simple website which listed five organizations doing good work. Using the ICICI network and online banner advertising Give started reaching out to potential donors.

The first eight months were a disaster. GiveIndia managed to raise Rs 1.31 lakhs in 34 transactions. On January 26th, 2001, the Gujarat earthquake happened. The site crashed, after receiving three million hits in a single day. GiveIndia raised Rs 97 lakhs in one week.

“We set up an earthquake relief fund and at that time, were the only online vehicle available to donate in India.” The sad truth is that when something happens, people give far more that is required. What they don’t realize is that a country like India is a daily living disaster. Diarrhea is a much bigger disaster than earthquake, tsunami, cyclone, the Orissa cyclone, all of them put together.”

So January 26th, 2001 was really an aberration, not a ‘turning point’. In the next financial year, a year without an earthquake, GiveIndia raised only Rs 25 lakhs. However the amount of money raised was not the only measure of success of the project.

Venkat explains: “We evaluate Give on the basis of three parameters. One is the amount of money we are able to channel. Second is the number of donors we are able to engage. Every individual donor chooses what he wants to do through GiveIndia, and therefore we can’t measure the impact at the end destination.”

GiveIndia believes that a large number of individual donors making choices will collectively make a much better basket or portfolio than one smart foundation giving grants. So its own success lies in getting more and more people engaged. Getting more and more people to care.

“You must keep in mind that the amount of money we will raise will always be insignificant. Even if GiveIndia becomes rabidly successful and raises Rs 1,000 crores a year, the Government of India give Rs 18,000 crores every year to NGOs alone.”

So it’s more about instituting a culture of giving.

“Yes, but more important that that is the idea of building ownership. Why is that the tax rupee does not get used effectively? Because most of us look at taxes as a license to exist. We are paying taxes and telling the government, ‘I don’t care whether you are doing anything with this money or not, leave me alone’.”

The middle class response to every national problem is, privatize! Government schools suck, so we put our kids in private schools. Water starts getting bad, so we consume mineral water. In the year 2006, India’s expenditure on water, privately paid, exceeded the combined water budgets of all municipal corporations!

At this point I wonder if I am speaking to Sitaram Yechury but Venkat is simply stating the problem. And he's not got a closed view about the possible solutions. So privatize all you want but do not disconnect. Do not abscond from your duty as a citizen.

"That is why Givelndia insists that everybody has to choose where their money will go. Because even making the choice that I think education is more important than health, or livelihood is more

important than education, means an individual has thought about and acknowledged the problem!"

Every individual donor gets a report describing how their money was used. Which makes people realize that even a little contribution can make so much difference. For example, it takes just Rs 180 to give a smokeless chulha!

"When I was a kid, I have seen my mom sometimes use firewood, and I remember how much she used to cough. So imagine somebody else's mother, three times a day in the village, is inhaling firewood, coughing, coughing, coughing! And we have spent more than hundred and fifty rupees on this coffee right now! That's all it takes to change!"

Backing all this passion and conviction is systems and management science. Givelndia now certifies 120 voluntary organizations. It provides the due diligence and the platform. And Venkat believes that the market will correct everything else.

"If an NGO comes and gets listed on Givelndia today, they typically start getting some amount of money every month. Somebody will get 1,000 rupees a month, somebody will get five lakh rupees a month. What they start seeing is the power of engaging Individuals as against depending on one large donor (as charities have traditionally operated). They see the value in being transparent In their accounting."

While earning a 'profit' is not crucial for Give, the goal was to ultimately become self sufficient. Today 94% of Givelndia's revenues come through the transaction and service charges levied to donors. Only five per cent of the expenditure is borne from the seed grant that ICICI had initially provided.

"My idea is that in the next 3-4 years, it should be a 100% viable organization standing on its own feet. If my cost of fund raising is about 20 per cent, ICICI wouldn't bother too much. But an individual donor, giving 1,000 rupees will jump up and down and fuss about it. And that's exactly what I like. Because his pressure will drive us to be efficient. It will not give us the space to take things easy and set unambitious goals."

That is why much of the Rs 4 crores provided by ICICI after the initial funding (Rs 72 lakhs) is lying unused. The challenge is to not need to use it!

In 2007-08, Givelndia expects to channel roughly Rs 18.5 crores from 50,000 individual donors. Of these, 25,000 are 'payroll giving' donors. This is a program Givelndia has been promoting to corporates where employees can choose to have a small fixed amount deducted from their salary and channeled to a cause of their choice.

'Payroll Give' was born out of the insight that people want to give, but it is not high on their priority. So, we will have to reach them, and not vice versa. But how? The most common method of fundraising used by NGOs is face-to-face. This is horribly expensive. For every 100 rupees, the cost of raising the money is 40-70%.

Venkat's analytical mind broke down the problem.

"The cost of raising funds can be broken down into the cost of establishing credibility, cost of doing the transaction, and then the cost of servicing the relationship with the donor. The idea of PayrollGiving is - I go into a company and the GEO sends out a mail to all the employees saying that we have signed up for this program. Cost of credibility is zero."

"The second thing with Payroll Giving is that you acquire a customer once, but he stays with you for a lifetime. Once he has signed in, by default he is on the program. So the only thing left is the cost of servicing the donor. You have straight away brought your cost down substantially. That's one of the reasons why it works."

Currently more than 20 companies including HSBC, HDFC, ICICI bank, YES bank, Deutsche bank and many others have signed on. But Venkat admits, it was not an instant, runaway success. Few new ideas are!

The initial pitches were made to friends and well wishers. In the initial one-one and a half year Payroll Giving saw market response but struggled to crack the sales model. Eventually they built a classic retail sales organization driven by targets. But it remains an intense effort. One mail from the CEO and HR department is not enough to move 10,000 people. You need to go and meet people from desk to desk - there is no two ways about it!

The power of a person-to-person sales pitch is never to be underestimated. It's one of the arrows in the arsenal of every entrepreneur, unmatched by automation and corporate-ization.

The most visible form of fundraising however, remains the Marathon. Givelndia is the official charity partner for the events in Mumbai and Delhi with around 15,000 individuals raising funds through this channel.

"We saw how marathons in the other parts of the world raise a lot of money. Standard Chartered bank was sponsoring the Mumbai Marathon and Procam was organizing the event. We went to them and said, 'Why don't you let us use the event as a platform? The benefit is that your event gets a nice feel, a social conscience. You will find it easier to push things through with government and the media, press, everybody will be more interested.' So they got excited."

In 2007, the Mumbai Marathon raised Rs 7 crores and the Delhi Marathon Rs 1.5 crores.

65% of this was through individuals, as that is Givelndia's focus.

"We don't want to focus on companies. See, companies don't change the nature of a country. It's individuals who change the nature of the country. So if you want to change the caring nature

of the country, you have to work with individuals."

And thus came the idea of raising pledges. Instead of an individual simply donating to charity, he or she would run for a cause. And raise money for this cause from other people.

The best thing, exults Venkat, is that there is zero event organizing cost, so the total fund raising cost for Givelndia is a mere 3.5-4%. Which is an industry benchmark!

Lastly, around 5,000 people give purely through the online route, contributing 15-20% of Givelndia's overall inflows. The big challenge now is scaling up, and this requires investment.

"We are investing almost a crore in IT. Our payroll program has worked only because of technology. People sign on and sign off online. We process that and send the company a file which they upload into their payroll processing software, whichever software they are using."

Payroll Giving is not the first attempt of its kind but it has worked because it understands the end user's needs. Then there remains the challenge of attracting good people.

"By NGO standards we pay reasonably well. But of course nothing close to the corporate sector. Also we require people who are going to do very corporate type of jobs. They are not working with children and receiving emotional fulfillment on a daily basis. Yet we do attract people with a huge sense of commitment."

There are many high caliber professionals willing to work part time. Finding such people willing to work full time is the challenge.

"In many ways, what Givelndia is today is thanks to people like Mathan Varkey (who was Triton's Media Head) and Pushpa Singh (Sr Mgr at Anagram) who gave up successful and lucrative careers to work for a cause," says Venkat. There are at least 15 such people in Givelndia who've said 'no' to megabucks for a chance to make a difference.

So what is the future looking like? Very bright!

"I think the next generation has a much greater orientation of giving. We have all seen difficult times in childhood. So there is this fear that something could happen, there could be a recession etc etc. But the youngsters today are so confident, so secure. They feel confident that we will be able to take care of ourselves, so let's share a bit."

In fact, at BPOs like Genpact and WNS, young kids, 22-23 year olds earning Rs 6,000 have signed up to donate Rs 100 a month. And conversion rates in these BPOs are 70-75%!

So the culture of 'giving' does seem to be taking root.

Venkat recalls Givelndia's first ever annual report, which contained a paragraph which he wished to see in the 2020 annual report. It's a letter which read as follows:

Dear Stakeholders,

We are delighted to inform you Givelndia has closed down.

Donors are now active, they are finding NGOs, they are engaging with them, they are giving money directly and they don't need GIVE INDIA.

"We love what we do, but ideally we are an undesirable element. The existence of a Givelndia is a reflection that people in this country are not able to do what they should do on their own. There is a need for people like us. 1wish there wasn't. So we could also go and make money in the corporate sector."

Not that such a thing will ever happen! Already Venkat is deeply involved in a company called E-I or Education-Initiatives run by DD and Sudhir. In fact, he draws no salary from Givelndia at all.

"I spend 25-30% of my time on EI. EI pays me, I got a big salary hike this April - from 12,000 bucks, I now make 20,000 bucks. I stay with my parents, so that's more than enough."

"The best joy comes when we are able to do something and prove an idea. Right now we are working on a product called ADEPTS. It is an online self learning tool, that kids can use to teach themselves a subject."

"We are doing it with great depth of understanding. Really sophisticated statistical tools. Only four or five people in the world are using those kind of tools. We have a depth and granularity of how a child learns. That's fascinating, commercial success is actually not important."

And yet, you know it will come. And that Venkat will eventually move on.

"Next August I will be out of Givelndia," he promises. "I genuinely believe that I am now counterproductive to the organization."

As usual, there are no definite plans but you can be sure something new will fascinate him. But, of course, it will be all about making a difference.